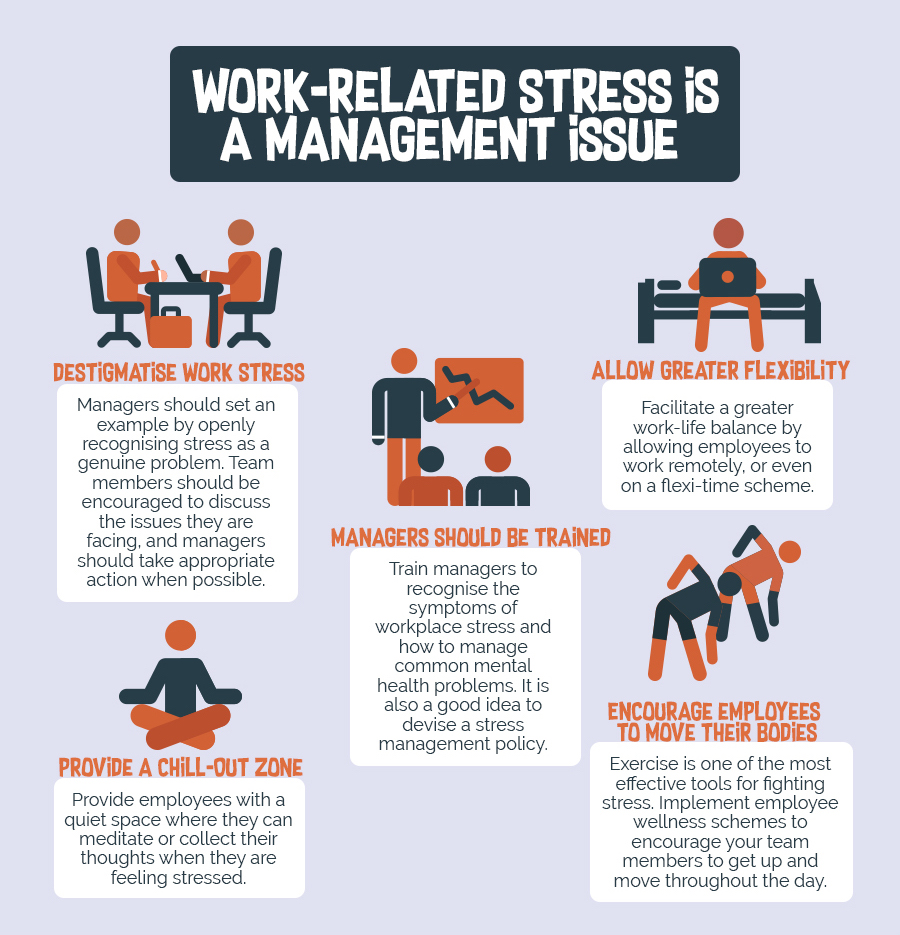

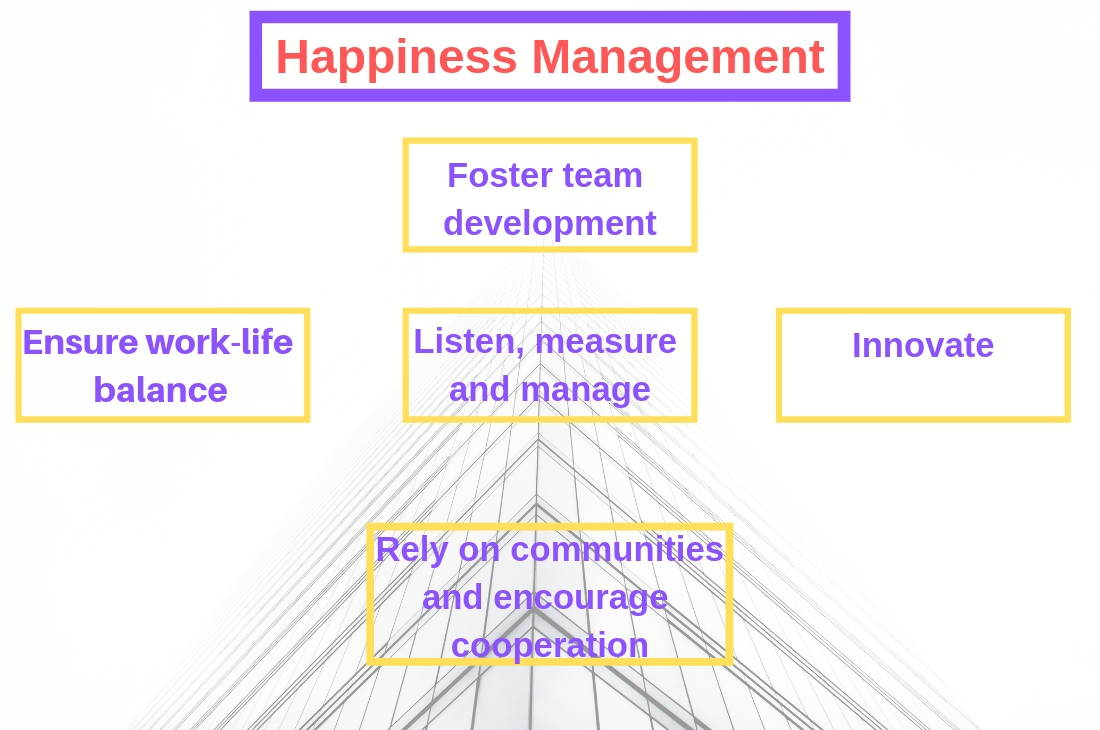

It is not only an individual problem: the most effective remedy against burnout syndrome is a management capable to foster wellbeing. Discouraging workaholism, respecting the right to disconnection, creating a horizontal and transparent communication process, investing on spaces and experiences: these are some of the best practices a good manager has to follow in order to prevent, recognize and take action on the burnout syndrome cases that might arise in the office.

More arbejdsglæde (in Danish, “happiness at work”) and less “Karoshi” (in Japanaise, “death by overworking”).

This has to be today’s management’s motto. Two words that express two different cultural ways of approaching working, underlying how the cultural dimension is crucial in a company.

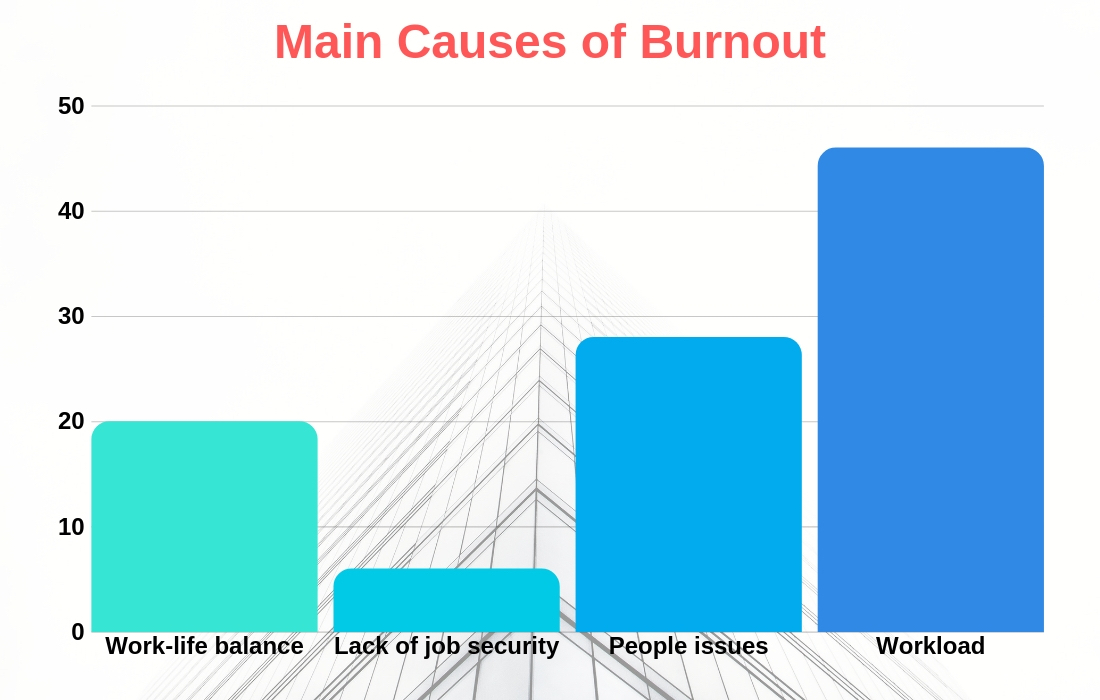

The burnout syndrome has we already said in the previous article, is the embodiment of a wider organizational problem: one or more employees that feel constantly overwhelmed by their job instead of feeling satisfied by it, is an important signal that the management has to change something.

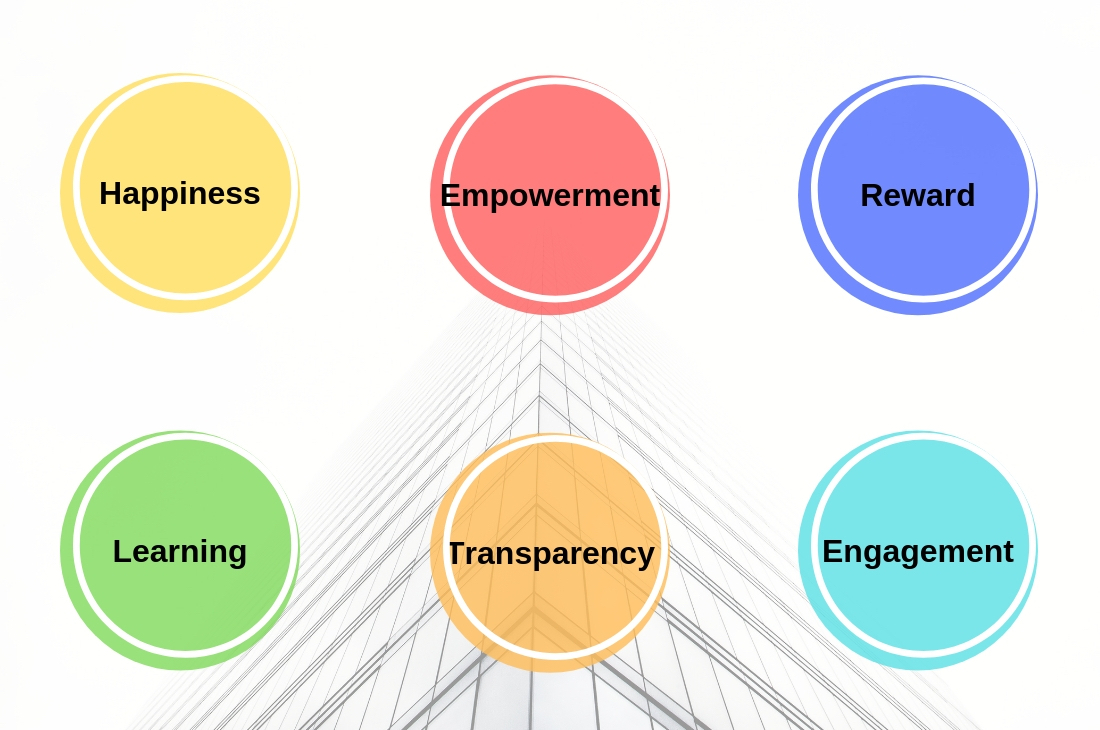

The goal, as the Canadian Great-West Life Centre for Mental Health in the Workplace underlines, is to create a “Psychologically Safe Workplace”, where every effort must aim to safeguard and implement the mental and physical wellbeing of the people. Every manager, today, is assessed on the basis of the awareness of his impact on his team, of his ability to listen to and to face the needs of the employees and of the wellbeing and good atmosphere he manages to create.

If theoretically it sounds easy, practically speaking it is not a piece of cake. For instance, how can a manager reward a member of his team for the hard work he has been doing, without encouraging unhealthy behaviour?

Denmark, the first country in the world for happiness at work, can be a good touchstone.

Lock yourself up in the office and work for more than 80 hours per week is rather frowned upon in Denmark.

A recent study run by the Harvard Business Review has shown how a “highly engaged” employee out of 5 is at risk of burnout. In order to face one of the main problem new technologies have brought in the matter of work-life balance, the Italian Agile Working Act of 2017 recognized the right to disconnection, meaning the right to not be on call 24 hours a day. The right to disconnection also means to create dedicated spaces to allow workers to “disconnect”, like break and relax areas and company restaurants, that take care about their mental and physical needs. As the Evolution Design’s Executive Director Stefan Camenzind said: “Once falling asleep at work was to be blamed, now, instead, who doesn’t do a nap at work is considered irresponsible”.

A horizontal and transparent communication and a less hierarchical organization are key features of Danish offices.

Investing on intangible resources, such as team-building experiences, as theatre or sport in the company, promotes collaboration and sharing, consequently fostering an environment where the sense of trust helps everyone to develop their own talent.

Trust allows the management also to prevent and to become aware of situations that could go unnoticed: if a worker realizes that a colleague is suffering from workaholism or to much stress and anxiety, it should feel free to inform the manager or the HR.

Eventually, it is important to create a human-centred system: the lack of empowerment, the feeling not to be important for the company and unresolved or latent conflicts are the main causes of the burnout syndrome to arise.

Lifelong learning and the opportunity of constant training to improve one’s own skills is where Denmark spend more than any other European country.

The professional growth creates a greater self-efficacy in the employees, lessening the sense of anxiety created by the unpredictable and uncertain contemporary economic situation.

In short, personal wellbeing in the office is not just a personal matter. As we have already claimed in other articles, productivity, emotions and mental health are strictly linked. Burnout syndrome cases, nowadays, are clear symptoms of cultural management that need to be changed.

Text by Gabriele Masi.