After attending the IM Master and graduating at the Design Academy Eindhoven in 2009, the two Italian designers Simone Farresin and Andrea Trimarchi, chose to stay in the Netherlands.

They have founded in Amsterdam their own design studio Formafantasma. The name means “ghost form” and is already a declaration of intent, as they explain “It refers to the way we work that is not guided by a form exercise, but based on research. The form is the result of a process. In this sense it can change from time to time.”

The column “Ways of Designing” by WOW! presents two real pioneers of restorative design, focused on design approaches for e-waste management.

Since 10 years Formafantasma has been consistently working on unexplored themes. The experimental research on materials, the importance of local traditions and the critical approach to sustainability are the pillars of their design.

They collaborated with some of the most important fashion brands and soon became internationally famous; their projects have been exhibited in some of the most important museums in the world, including MoMA, London’s Victoria and Albert, New York Metropolitan Museum, Chicago Art Institute, Center Georges Pompidou in Paris. In Italy, in addition to the projects for Flos, they presented at the Triennale di Milano “Broken Nature” their meta-project Ore Streams, a significant example of restorative design.

Achille Castiglioni quoted “We have to design starting from what we must not do”. In your opinion what should not be done?

Design based on fashion. Design based on your own ego. Design to express individual desires. Design to have fun. Design to sell the most. Design gadgets.

Who was your Design Master?

Enzo Mari. Obviously form a master you learn but you also let him go. You develop your own ideas. We never fully love our Masters.

Which elements and experiences featured your design approach? Are there some products that better represent your approach?

We are very proud of Ore Streams. The project was developed for the NGV Triennal initiated by the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and for the Broken Nature Exhibition at Triennale di Milano curated by Paola Antonelli.

Initially we wanted to focus on the mining of minerals because Australia is still one of the few first world countries that has its economy still largely based on mining.

We wanted to investigate the relation between the sourcing of materials and their transformation into products. The earth’s surface has been mined for millennia in search of resources such as metals and minerals to fulfill our production demands.

In fact, forging metal changed the course of history: bronze empowered humans to weaponize and gold facilitated local and then global trade.

Even at this very moment, new cavities are being hollowed out, while existing excavated sites are abandoned or re-filled with new earth: a superficial recompense.

Our human greed for metals has grown to such an extent that by 2080, the biggest metal reserves will not be underground. Instead, they will be above the surface as ingots stored in private buildings or otherwise circulated within products such as building materials, appliances, furniture and an ever-growing market of consumer electronic products.

Because of this we decided to focus on the recycling of metals, because in the near future the majority of materials will come form recycled sources. Obviously this is great, nevertheless on the surface of our planet, rivers of ore in the form of these discarded materials stream freely as if in a continuous, borderless continent.

Efforts to recycle this complex hardware remain new, uncharted and contentious. New logistic structures, technologies and cross-country alliances are being forged to allow for the renewal of metals at the lowest expense. As this shift ensues, the mining industry will be permanently altered. We will enter a new phase, where above-ground scavenging will out-perform and out-value digging below the surface for raw material.

We decided to specifically focus on e-waste because it is at the moment the fastest growing stream of waste globally. Moreover because of the complexity of recycling digital tools, a lot of these products are illegally shipped in developing countries were often recycling technologies and regulations are not in place. This is obviously a problem both for the environment and the worker.

Why and how should design take into account the problem of electronic waste?

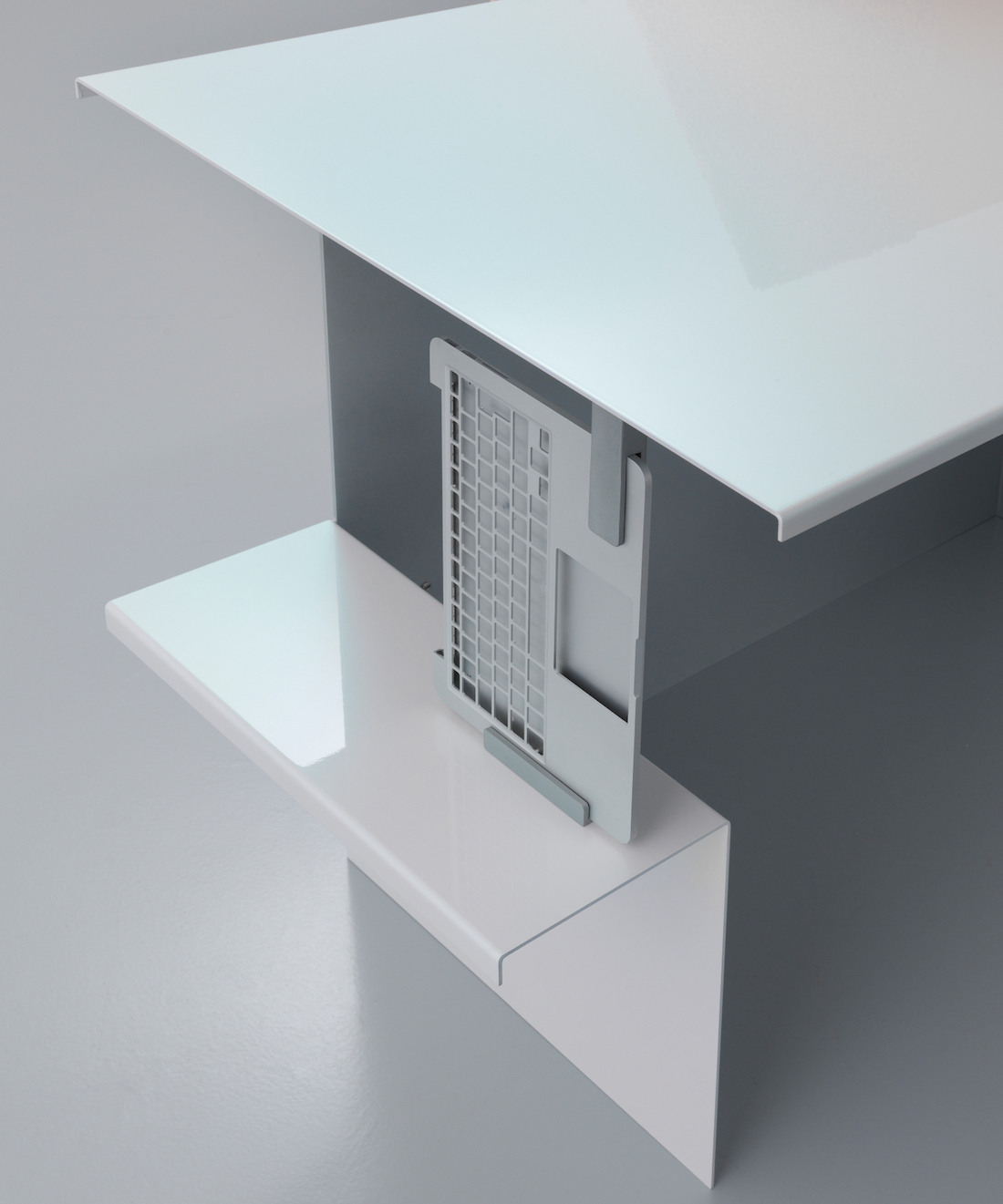

The exhibition at Triennale includes a animation where we make use of 3D rendering as a tool to visualize possible strategies for the repairing and recycling of electronics.

The concepts displayed are conceived considering the recycling technologies now in place and the limitations of facilities across developed and developing countries.

I’ll give you some examples:

A common trend in electronics is the miniaturization of products. This has increased the already wide-spread use of glue to attach components in order to save space.

Designing objects with space efficient connections/clamping systems will guarantee precise separation of materials.

The most common problem for both recycling in developed and developing countries, is removal of batteries and hazardous components.

The use of visual recognition technologies in the sorting of waste has great potential but remains unexplored.

Electric cables are very commonly covered in black rubber. Yet, due to the dark colour and opacity of the surface, they are not recognised by visual detectors. A simple design choice such as using coloured rubber or even a patterned surface, could dramatically improve the recycling of the copper used in electric cables;

Too often e-waste objects are not labeled with information about their materiality. Constant development of new polymers makes it difficult to identify materials and separate them precisely.

In developing countries, rudimentary and oft toxic methods are used to determine what a material is, for instance burning is used to understand the composition of a material based on how it melts and the colour of the flames.

As a response we envision a scenario in which objects would be delivered to recyclers with an embedded digital material passport in the form of a QR code and universal colour coding.

So Ore Streams is a complex project and the objects presented at the Triennale are only a small part?

The intentions of Ore Streams are multiple. With the videos and the interviews we are researching the complexity of the topic and the problems in recycling. We also propose with a animation a series of strategies that can be applied when designing products to facilitate both repair and recycling.

At the end we also design a series of objects. It was part of the commission we received by the National Gallery of Victoria who was the original commissioner of the work.

The objects are only one part of the work. The most important are actually the videos. In this moment we also published the website OreStreams.com in it we publish all our research so that possibly other people can appropriate it. The main driving force behind the recycling of e-waste is the recuperation of precious metals used in circuit boards, like silver and gold.

The singular user (we hate the word consumer) is not responsible for the direct recycling of electronic waste since these objects contains hazardous components that must be handled by professionals. Nevertheless what is very important is to make sure to deliver broken electronics or to the producers or to collection centers in the city.

At this moment only the 30% of electronics is correctly recycled while the rest or ends up in the wrong recycling facilities or illegally exported in developing countries.

What the majority of people don’t know is the the European Union clearly legislated on the responsibility of e-waste recycling and that is on the producers. The producers should be responsible for the collection of broken electronics.

How new users life styles and ways of working -Millennials and Generation Z- can impact on product design?

We don’t really care of oversimplified sociological ideas appropriated by marketing. We just hope these new generations would transfer from consumer to (as often mentioned by Paola Antonelli) in citizens.

How has the workspace vision changed in the past few years and what scenarios and evolutions do you expect for the office and the ways of working in the near future?

For long time the inform way of working was the way to go. It is still the same but there is more and more desire for privacy. The open space turned into a nightmare. We already see a return to more private, individual ways of working.

Captions

ExCinere by Dzek is a refined collection of volcanic ash-glazed tiles suitable for both interior and exterior surfaces; the result of more than three years of research and experimentation. Dzek and Formafantasma have collaborated to produce a useful architectural product that makes full use of volcanic lava’s material properties. “Mount Etna is a mine without miners; it is excavating itself to expose its raw materials.”

Wireline by Flos uses the power cable as one of the main design features. Flattened to resemble a belt made of rubber and hanging from the ceiling, the cable holds a ribbed glass extrusion containing a LED light source.

On a material level the lamp plays on the contrast between the industrial feeling of the rubber and the sophistication of glass.

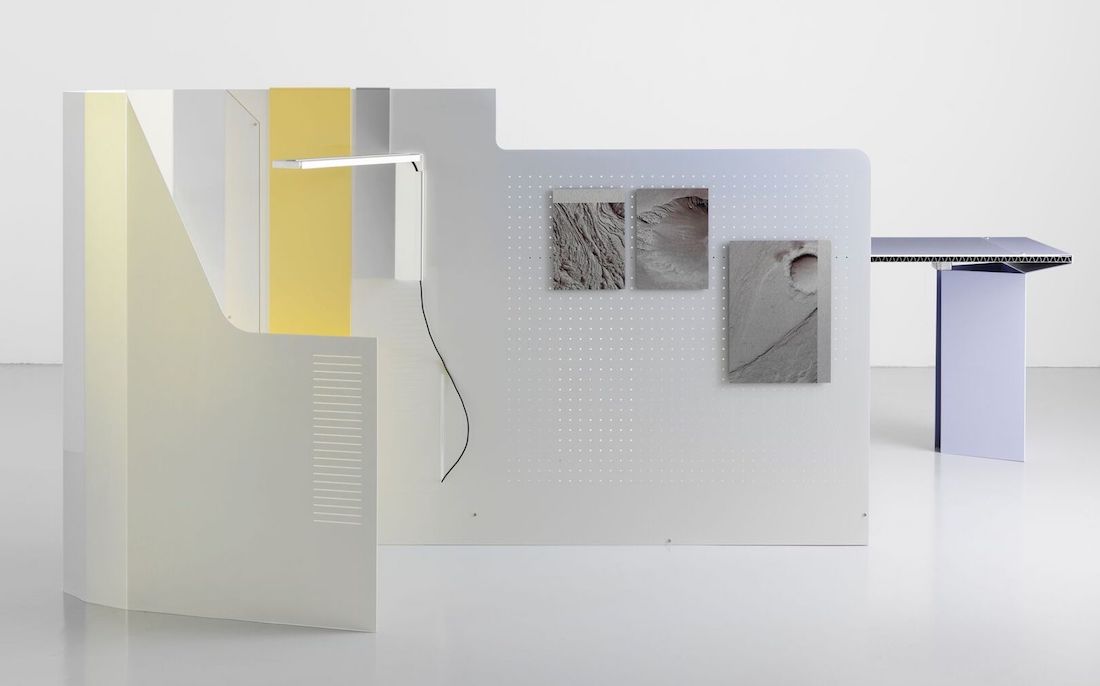

Ore Streams is an investigation into the recycling of electronic waste, developed over the course of three years (2017-19) and commissioned by NGV Australia and Triennale Milano. The project makes use of a diversity of media (objects, video and animation) to address the topic from multiple perspectives. The goal is to offer a platform for reflection and analysis on the meaning of production and how design could be an important agent in developing a more responsible use of resources.